The Man - Alfred Zampa

Al Zampa’s life, his entire 95-years of life, was filled with excitement, pride, enthusiasm, danger, and a fierce love of his profession. How many amongst us, at the end, could honestly say, as he did, “I had a hell of a time!”…and be willing to share the experiences and stories to prove it?

Zampa’s parents came to America in the early 1900’s from Ortucchio, Italy, a small village about a two-hour ride east of Rome. People from Ortucchio are said to be “strong, but with good hearts.” Al Zampa seemed to inherently realize that, and lived his life accordingly.

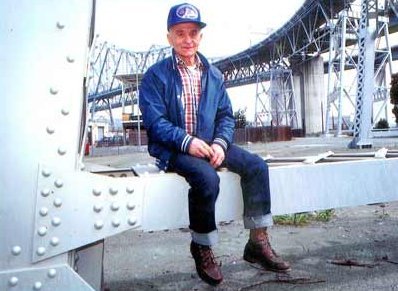

Page upon page has been written about Al Zampa the iron worker, and about Al Zampa, a member of the “Halfway to Hell” Club. Photos at the Crockett Historical Museum chronicle his life from a young, buffed iron worker to a 90+ senior citizen, whose spirited character was still undeniable.

Zampa was born March 12, 1905 in Selby, California, about 30 miles northeast of San Francisco. He had two brothers and two sisters, and was the oldest of the five. The family moved directly across the highway to Tormey in his early childhood.

After graduating high school he worked for a short time at the C&H Sugar Refinery, and then became owner of a meat market in Crockett. The path his life would take was determined the day a friend told him jobs were available on the construction crew of the Carquinez Bridge. Who would have known the day the brash 20-year-old began work as a rigger and pile-driver that a bridge, built over 75 years later would be named in his honor? Certainly not his father Emilio, as he tried to dissuade him, “bridge work is too dangerous,” Emilio told his young son, “it’s for desperate men.”

What transpired between 1926 and 2003 is what makes Al Zampa a legend to some, an enigma to others, and a dad and grandfather to those who knew him best.

Iron workers who worked on the first bridges were in a class all their own. They were, generally speaking, hard working, hard living individuals whose love of excitement, adventure and daring defined their lives. Although admittedly a little leery in the beginning, it didn’t take Zampa long to feel comfortable working “with the devil and with angels.” He obviously took to heart the words of his first boss when he said, “You’re a natural. You could work on any bridge.”

And work on bridges he did. From Stockton, California, to Arizona and Texas, he followed his dream. Early in the 1930’s he returned to the Bay Area to work on the Oakland-San Francisco Bay Bridge, which always remained his favorite. “Nine bridges in one and a tunnel in between. It’s got approaches, trusses, girders, a camel back, a cantilever span, two suspensions, and a tunnel. We laid the piers 240’ deep on the Oakland side…those are still the deepest piers in the world.” The pride of many an iron worker is still evident in his long-ago words.

The dangers were ever present; during the building of the Bay Bridge, 24 men were lost, many of whom he knew, as they went “into the hole,” the phrase for a drastic, often-times fatal fall. Zampa, wearing an “Iron Worker Local 378” cap, is quoted in a 1986 San Francisco Chronicle article, explaining the fact that great bridges were hand built. “The rivets were heated red hot on a forge and tossed up, sometimes 90 feet, and caught in a small, funnel-type cup; they were inserted and driven home. It had to be done just so, ‘cause if the rivet got too cold, it wouldn’t create the proper fit.”

Zampa continued, “Anytime someone got killed on the job, we’d go jittery and go home for the day. We’d wonder, is it our turn next? If we got hurt, we couldn’t get no insurance, no welfare or nothing, until the union came up. I don’t know where I’d be without the union. I’m on a union pension.”

When accidents occurred, or on days work was prohibitive because of weather conditions, it wasn’t unusual for Zampa to bring a large group of iron workers home with him, where for hours they would have noisy discussions, drink wine, and enjoy the pasta his wife Angie was quick to prepare. It was a typical Italian household; friends were welcome, stories were exciting, and food was plentiful. It is little wonder that Zampa’s two boys would enter the same profession, much to the chagrin of their apprehensive mother, who knew all too well the corresponding dangers.

Zampa joined Local 377 of the Bridge, Structural and Ornamental Iron Workers in order to work on the Golden Gate, which was the first bridge in the area to be built with an all union labor crew, and the first to employ safety nets and to require hard hats. “I just knew it was gonna be a great bridge. No one had ever seen a bridge like that one,” he reminisced in a profile in “Image” in 1987.

“Net Grounded; Bridge Worker Falls; May Die” reads an October 20, 1936 headline. That bridge worker was Al Zampa, whose “turn into the hole” had come. While working as a connector, stepping from stringer to stringer, he slipped on the wet iron, flipped over backwards three times, and hit the net. The loose net hit the rocky Marin County shore, resulting in four broken vertebrae, a 12 week stay at St. Luke’s Hospital, and two years living with a steel back brace for Zampa. As soon as he was able, he walked a girder of the then unpainted Golden Gate Bridge, to prove to others, as well as to himself, that the fall had not diminished his confidence. The fall made him a full-fledged member of the legendary “Halfway to Hell” Club.

Unable and unwilling to remain idle during his long recovery period, Zampa operated rental boats out of Joseph’s Fishing Resort in Rodeo, California, and a passenger boat along the Carquinez Strait. By this means, he had found a way to support his family while continuing to keep watch on the progress of bridges, albeit from below rather than from above.

Shortly after returning to work, Zampa met an old acquaintance, Tommy Barbose. Talk quickly turned to the “old times,” when they played baseball in Crockett. That conversation led to the organization of the area’s first baseball league, the Tri-City Baseball League for local youth, organized and sponsored, in large part, by Barbose and Zampa. The league was active until 1953, and included teams from El Sobrante, Pinole, Rodeo and Crockett. A plaque at the Crockett Historical Museum shows a smiling group of young baseball players and states, “Thanks, Coach.” The coach of the pennant-winning Crockett team was none other than Al Zampa.

Although the Golden Gate had been completed by the time he fully recovered, Zampa returned to work out of Local 378 Oakland. He worked on the overhead cranes that can still be seen at the Mare Island Shipyard, and on the power line towers that connect Crockett and Vallejo over the Carquinez Strait. He continued to work on other area bridges, including the Benicia Bridge and the Richmond-San Rafael Bridge. He took pride in the fact that he worked “side by side” with sons Gene & Dick on the second Carquinez Bridge, which was completed in 1958. He considered the two Carquinez Bridges the most important because they were so near his hometown.

Zampa worked as an iron worker until his retirement in 1970, at the age of 65. “It was important to him to be a connector (the exalted position he held for years; being a connector is reserved for the most daring, seasoned and respected of iron workers) on the last day he worked,” said his grandson, Don Zampa, “to prove he could still connect, and that he was retiring out of convenience rather than necessity.” His highly competitive nature was still very much in tact, and remained with him throughout his retirement years.

For many, life changes considerably after retirement, and work slowly fades into the background. But with two sons, and then three grandsons working as iron workers, Zampa’s interest in bridge building was always a part of his daily life. In 1987, on the 50th anniversary of the Golden Gate, and the 60th anniversary of the Carquinez Bridge, Zampa was present and was quick to be quoted by reporters who intuitively approached the colorful Zampa… “To do bridge work, you gotta be as surefooted as a mountain goat, agile like a cat, and be able to climb like a monkey. I always say it takes 90% guts and 10% know-how. I’ve got my fingerprints all over that bridge.” In 2000, the replacement bridge over the Carquinez Strait was launched. Zampa. 94, was present to see the “beginning of the end” of the first bridge he worked on, the bridge on which he turned 21 years of age.

Words like “feisty, legendary, zestful, gutsy” and just about any other adventure-type adjective were used in numerous articles to describe Al Zampa over the years. But perhaps “The Ace”, the name given him by Isabelle Maynard in her play by the same name, best describes Al Zampa. The play, written by Maynard, was based on his life and was advertised as “An ironworker’s story of heroism, risk and recognition on the Golden Gate Bridge.” It was well-received on San Francisco stages, especially during the bridge’s 50th anniversary year.

The numerous proclamations, declarations and resolutions presented to Zampa over the years from various organizations and from politicians ranging from then San Francisco Mayor Dianne Feinstein to California Governor George Deukmejian reached a feverish pitch during the Golden Gate Bridge Celebration. The staunch, lifelong democrat undoubtedly took great pleasure in being recognized by leading democrats. He strongly believed in supporting labor-endorsed candidates, and never missed an election. Newscasters like Charles Kuralt and others from throughout the world interviewed the expressive Zampa, whose courageous spirit and perilous profession epitomized all bridge builders.

Alfred Zampa passed away on April 23, 2000, at age 95. Zampa was a builder of bridges; bridges that traverse the waters below, allowing travelers to explore the wonders of the world beyond. But Alfred Zampa was not a world traveler; he was content to live his life in Tormey, the small village in which he was raised. While he passionately sought excitement, while he climbed daily “to work with the angels,” he seldom traveled afar. Zampa excelled in the profession in which he was fiercely proud, but “The Ace” was firmly grounded by his family and friends.

How often have we ever considered the dangers involved in bridge construction, the fears, the lives changed by disaster, the lives lost? The story of Al Zampa is symbolic of all iron workers; may The Alfred Zampa Memorial Bridge long stand in tribute.

Diane Bottini Thomas

February, 2003